| Curator Paul Roth on Richard Avedon’s Portraits of Aging

| Mark Swartz

| Paul Roth is Director of the Image Centre at the Toronto Metropolitan University in Toronto, Ontario. Previously, he served as Senior Curator of Photography and Media Arts at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (where we were colleagues), and as Executive Director of The Richard Avedon Foundation in New York. Here, we discuss the book “Richard Avedon Immortal: Portraits of Aging, 1951-2004.” The exhibition will be on view at The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in February 2026 and at The Image Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University in September 2026.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What should a general audience know about Richard Avedon?

Richard Avedon was for many, many years one of the two or three most famous photographers in America, if not the world. And he was famous both as a fashion photographer and as a portrait photographer who worked for mass market magazines for many years.

What makes him different from other portrait photographers?

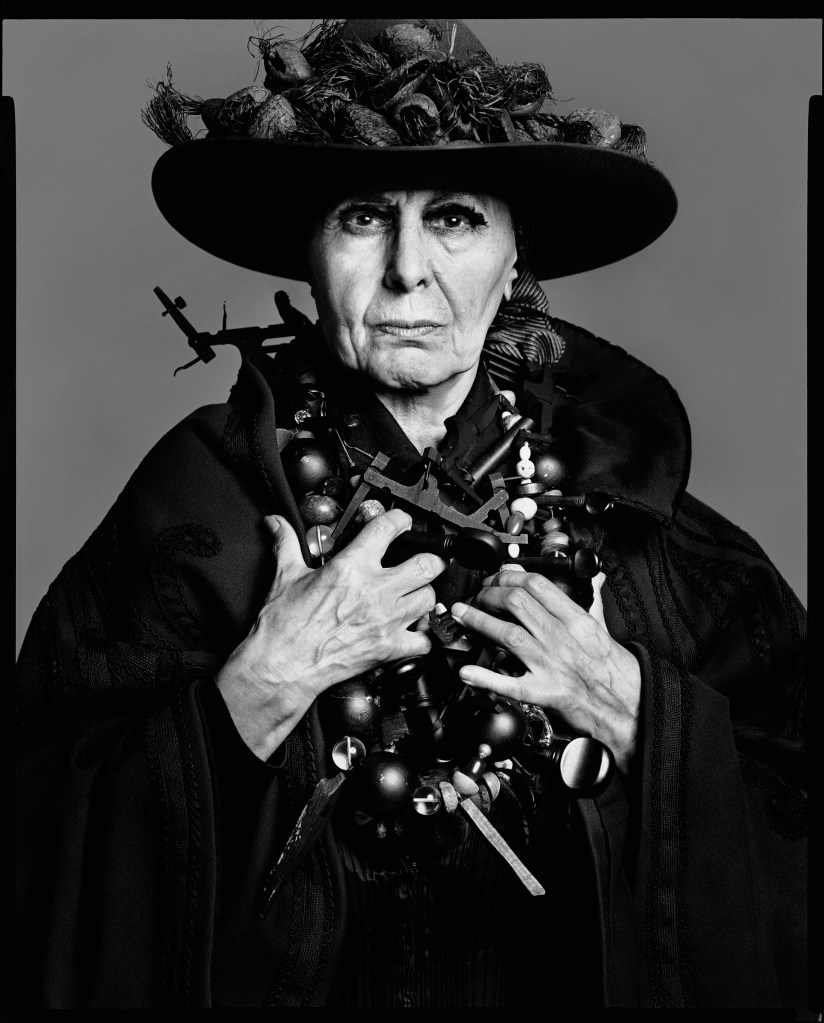

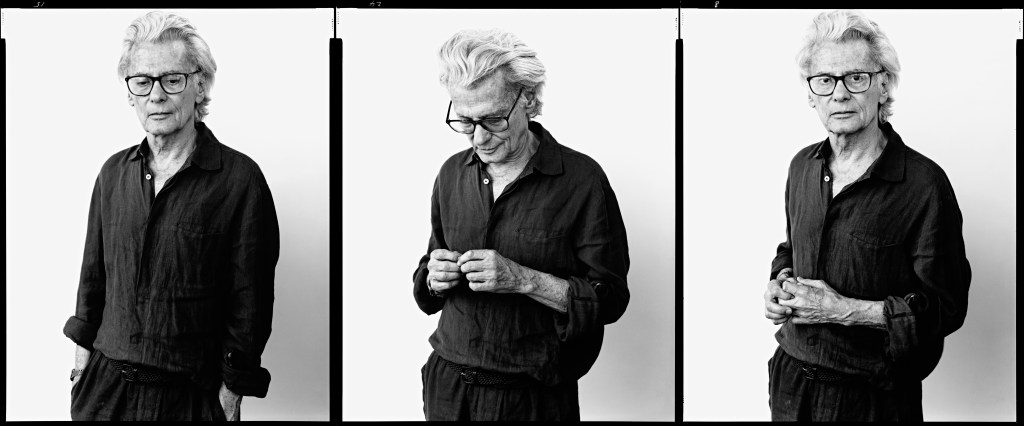

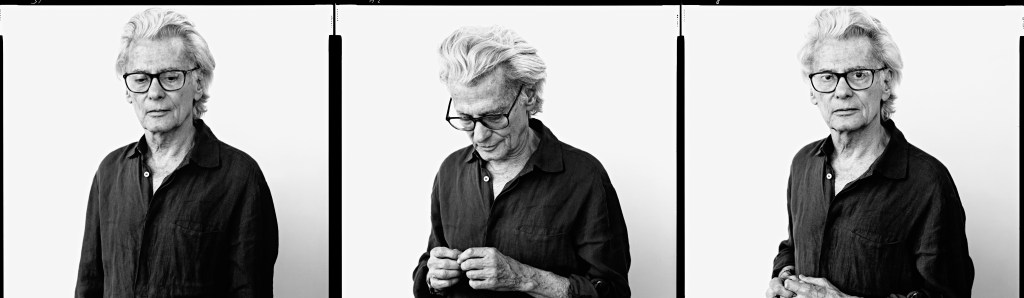

Portrait photographers flatter their subjects. We all know how common that is. But Avedon, from very near the beginning of his career, photographed people with a tremendous interest in the visual specifics of their appearance. Avedon was different from everybody I can think of in a very specific way, which is that he photographed people as though he was the director of a theatrical play. He would try to both direct and capture a kind of performance of drama, of visual drama in his subjects.

What made him interested in the drama of aging?

I think it’s partly because Avedon himself was afraid of aging himself. His pictures are about many things, as any portrait would be, but he was really interested in the way that life inscribes itself on the face and the body in ways that can’t really be articulated without the imagination.

How did that ambition show up in his technique?

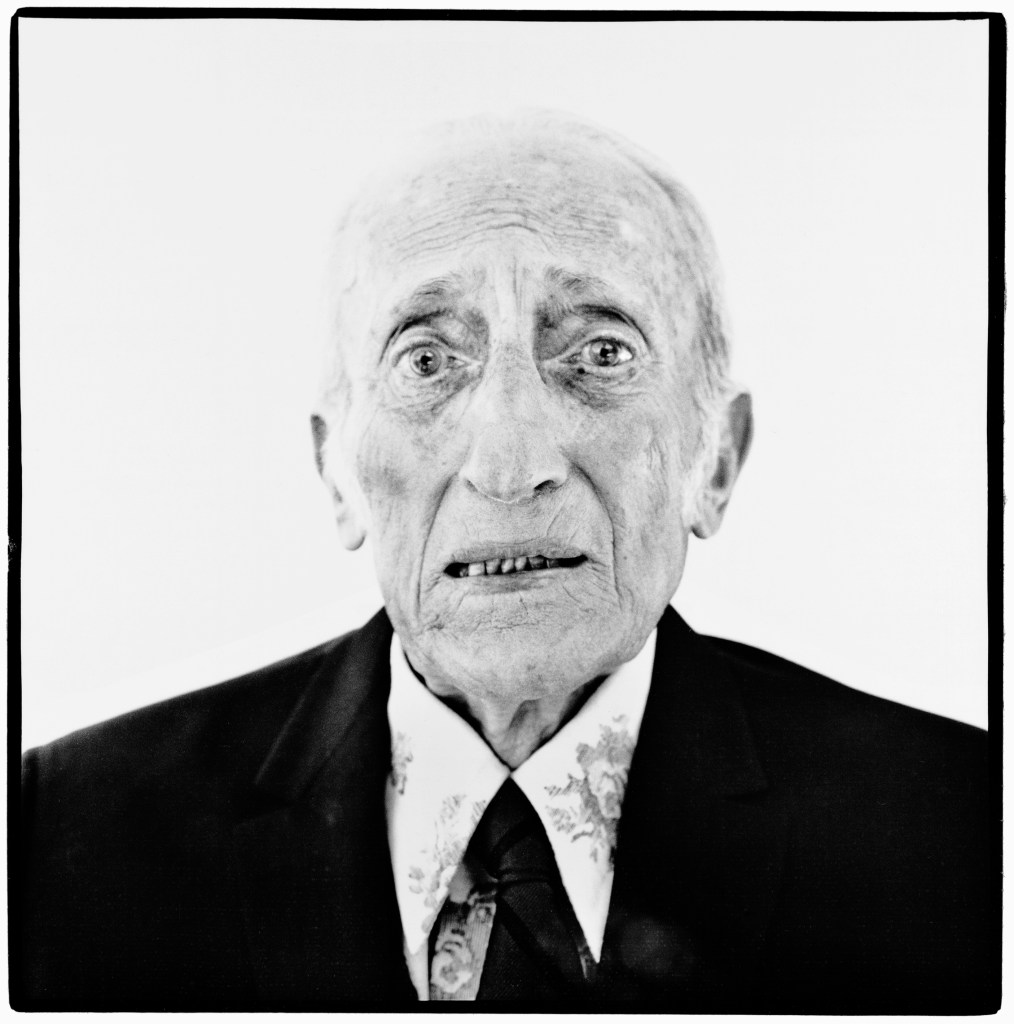

Avedon didn’t want to hide what people looked like. He would choose his lighting and his camera angles in a way that emphasized the signs of his subjects’ aging. And he would also do that in printing his photographs. And he would do other things, including retouching when the photographs were reproduced, to emphasize the aging face—whether that’s wrinkles or spotted skin or crow’s feet, the elasticity or dryness of the skin, or gray hair. These were all things that totally fascinated him.

How did he answer accusations that he was showing subjects at their worst?

Avedon often explained that he was not interested in making people look bad, that he was in fact entranced by their rough appearance, that he was trying to get at something deeper than the masks we all wear. Therefore, he had a series of photographic strategies that he would use in order to get at what he sometimes called ‘states of emergency’ in the face.

Is there a special sensitivity towards women, depicting women this way?

I don’t think that he deliberately treated women differently than men, but I think that the viewers—and I would say this is as true now as it ever was—have a greater expectation that women should be shown as beautiful. We all have our preconceptions that are gendered about aging. For example, men, when they look older, look “wise” or they’re to be celebrated for their strength as older men; while for women it might be perceived by the public that they should hide their wrinkles, they should put makeup on. He famously made a great and unsparing portrait of Rose Kennedy in 1976, and her son, Senator Ted Kennedy, attacked him publicly for how vividly it showed her aging. The suggestion being that you can’t possibly show a woman of this importance in this way.

Did you unearth photos in the archives that revealed something new to you?

The real discoveries for me were in the story of how Avedon photographed his own father in the last years of his life. At an early stage of developing the project, I decided that I wanted to write an essay about the making of that portrait series, Jacob Israel Avedon. And that meant understanding better his father’s earlier history, the troubled relationship between father and son, and then how the photographs were made, and eventually ended up in a seminal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974, less than a year after his father died. These portraits are extremely painful for most people to look at. You see this man aging towards his death.

Where does the title of the exhibition come from?

I started with a different idea for a title. Avedon had this wonderful expression, “the avalanche of age,” which, as he once elaborated, describes the face of an older person when it’s almost as though age is falling on them from above. For a brief moment, that seemed like the perfect title for the book and show. But the more I thought about the dual nature of the portrait photograph, the more I realized that while the photograph captures you at a particular moment of time, it also brings you into perpetuity. By photographing somebody who’s aged, there’s a suggestion of their mortality. Once the portrait is made, however, there’s a sense in which they become immortal. The great thing is that the title means both things at once—because “immortal” is one of those beautiful words which contains its opposite.

Mark Swartz is the founder of Aging in America News.

Leave a comment